Significance of Language Evidence

Words Reveal the Past

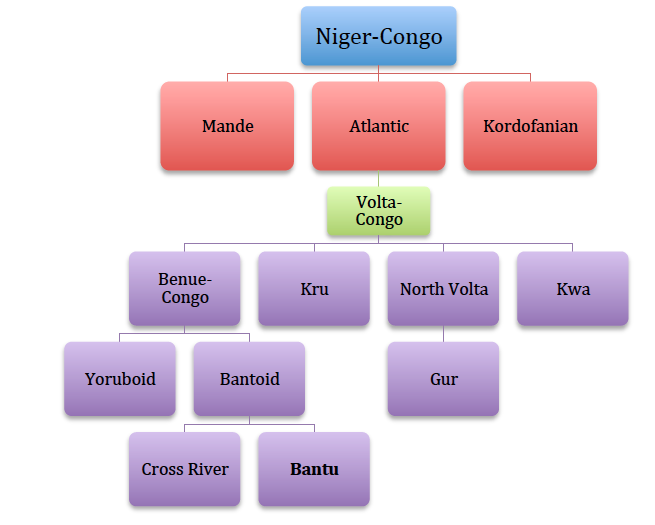

Human history and language history are fundamentally entwined. As such, language is a valuable means for making sense of the past. Bantu languages hold clues about their speakers’ histories in the words comprising their vocabulary. The reconstruction of the history of words falls under an approach called comparative historical linguistics, a field that uses language evidence to understand the relationships among distinct languages. For this kind of study, the linguist collects vocabulary sets as well as comparative grammatical and semantic data from related modern-day languages in order to systematically establish their relationships to each other and to reconstruct the phonology, vocabulary, and other aspects of the ancestral language from which those modern-day languages descended. Historian linguists apply the same systematic methods, but with a further ultimate goal—to gain insight into the human-driven changes in past societies.

Words Have Histories

Every language has a history. The words of a language are the essential tools and media for people to express and impart their cultural knowledge and to carry on life activities and cultural and social relations with people both inside and outside their own society. To uncover the history of a language and its words, a practice pioneered in the academic field called linguistics, is to uncover a very large body of evidence useful for reconstructing the history of past times and places. A great deal of what we know about the early Bantu past has come out of the research that historian linguists have spearheaded

Shifting Ancestor and Lineage Concepts in Linguistic Data

| Root | Meaning | Notes: attestations may vary due to regular sound change and meanings change over time in descendant languages. | Bantu Expansion Phase/Era | Sample Modern languages where words attested based on Guthrie’s regions and zones |

| *-dÍmu | Ancestor or Spirit | Later ancestor spirit *-zimu. Through regular sound change dI becomes zi in languages. | Phase One Expansions Proto-Bantu | Bisa, Duala, Gweno, Lwena, Lundu, Mongo, Rundi, Sukuma, Yao |

| *-jambe/ *-maybe | God | *Nyàmbe, a common attestation for Creator God, likely derives from *-amb-, Niger-Congo root that meant ‘to begin’, dating back to at least as early 5000BCE. | Phase One Proto-Bantu 3500 BCE | Herero, Kikongo, Lunda, Ngumba, Nzɛbi |

| *-dog– | To Bewitch | Evil behavior of humans has widespread attestations and varies on meaning only slightly. For example, it covers meanings such as witchcraft, to bewitch, to cast a spell, and poison in different locations. | Phase One Proto-Bantu circa 3500 BCE | Bemba, Chokwe, Kikongo, Kikuyu, Manyanja, Rundi, Shambala, Tebeta, Venda,Yao |

| *-gàngà | Religio-Medicinal Healer, Medicine | Widespread attestations suggest its early origins. | Phase One Proto-Bantu circa 3500 BCE | Bųlų, Chewa, Ganda, Kuba, Luyana, Makua, Mbongwe, Nįlamba, Nyakyusa, Venda |

| *-cuka | Matrilineage | *-suka termite hills, matrilineage | Phase Two | Bushongo, Lega, Ngonde, Nyakyusa |

| *-lungu | Creator God (term derived from a verb for ‘to become fitting, to become straight | from *-dúnŋ- reconstructed to Southern Kaskazi word for God meaning fitting, straight, right attested as *-lungu. Through regular sound change d becomes l. | Phase Three | Bemba, Kikongo, Kikuyu, Lumbu, Mbundu, Mpesa, Nsenga, Shambala, Xhosa, Yao |

| *-gàndá | Place of Settlement of Community | Root shifted to mean a settlement for a community. | Phase Two circa 3000 BCE | Ganda, Herero, Kikongo, Rundi, Sukuma, Zulu Tio, Teke |

| *-gàndá | Matriclan | Early on matrilineages were primary unit of organization. About 2000 years ago the root referred to a hearth where women maintained family alters and cooked. | Phase Two ca 2500 BCE | Sangha-Kwa languages Gabon, Namibia, Great Lakes |

| -kódò | Base of tree, roots | Not yet fully reconstructed, but widely attested Bantu root. | Proto-Bantu | Kauma, Kikongo, Manyanja, Songe, Yao, Zigua |

| -kódò | Grandparent | Phase Three circa 500 BCE | Giryama, Manyanja, Unguja, Yaka | |

| *-kólò | Matriclan | *-kólò from *-kódò tree trunk metaphor for matriliclan generalized to ‘clan’ among Kaskazi | Phase Four | |

| *lí-uba | Creator God (transfer old root for ‘sun’ to new concept of God) | Kaskazi on Lake Nyanza replaced mulungu term when adopted ‘sun’ as a metaphor for God from neighboring ??? and applied older Bantu root for sun to signify this new conceptualization. | Phase Four circa First millennium BCE | Yao |

| *-ded- | To Nurture | This more geographically limited root meant ‘to nurture’ in Sabi and Botatwe languages. In time, it came to mean ‘Creator God’ attested as Leza. In Kusi languages such as Nyanja and Chewa, it came to mean one who sustains life. The root *-deda is a causative form that meant ‘to be nurtured’ /d-/ became /l-/ while /-dIa/ became -/za/ in Savanna Bantu languages. | Phase Four Sabi circa 500 CE | Bemba, Ila, Nyanja, Chewa |

Words as Oral Documents

Language data can be written or oral. In this project the focus is on either orally communicated language data shared by modern day speakers, or data captured in dictionaries over the last century or so. The words of a given language are the central medium by which people express their knowledge, carry on their life activities, and impart to the next generation their cultural and social values. Language allows individuals to communicate with people both inside and outside their own society, thus language is also significant in revealing cross-cultural interactions historically. To uncover the history of a language and its words is to uncover a very large body of evidence useful for reconstructing the history of past times and places.

Words Change Form & Meaning Over Time

What we know about the early Bantu past has come out of the research that historian linguists developed to understand change over time in an artifact deeply tied to culture and highly reflective of world view — the vocabularies and languages people develop and speak. People use words to name and describe what they know and do. Words tend to persist across many generations unless there is compelling reason to eliminate terms. Changes over time in the meanings and usages of any given word reveals past changes in how people carried out the activities or understood the ideas depicted by those words. Historian-linguists examine the histories of vocabularies that are of cultural significance and historical interest. The histories of these kinds of vocabulary reveal the ways in which past people developed new ideas and shared established ideas. And they also shed light on the ways that languages have changed, persisted, or innovated to suit new historical contexts.

Comparative Methodological Approaches

Comparison allows one to make hypotheses. In other words, similarities might suggest shared histories. However, simply observing that societies share particular cultural features at the level of typology is not sufficient evidence by itself of a shared history. Similarities may derive from a shared earlier history or they may be the results of separate but parallel developments. This leads to the second and more significant way that researchers use the comparative approach. A researcher first applies to their comparative evidence the long-established analytical tools of the several relevant disciplines—among them, historical linguistics, archaeology, and comparative ethnography—to distinguish what are shared old cultural retentions from coincidental parallel developments. Finally, a researcher assesses and correlates evidence and findings of the different disciplines to determine if the conclusions are well supported by a robust body of evidence.

Core Vocabulary

Methods of lexicostatistic glottochronology involve a number of steps. First, a historian linguist must identify the phonological components of the modern-day cognate words in the different languages and, then, determine the systematic sound correspondences that explain those differences. The next step requires determining the percentage of core vocabulary that languages share. Core vocabulary tends to be more resistant to change because the words are fundamental and essential they are less likely to be innovated. Core vocabulary is commonly referred to as a one-hundred-word list. One-hundred-word lists hold terms spoken in nearly every language such as:: “all,” “bone,” “foot,” “night,” “nose,” “person,” and “water.”

People – *-ntu

An example of a 5,500-year-old Bantu core vocabulary word that speakers of the hundreds of Bantu languages and dialects have nearly all retained is *-ntu, an ancient proto-Bantu term that meant “people.” The prefix ba– is a noun class marker that signifies a person, thus with the noun class ba – with the word root *-ntu speakers emphasized the humanity and personhood of the signified. Person is a word and concept considered by linguists to be core or essential vocabulary. People do not easily give up or replace core/essential words in their language, unless there are compelling reasons to do so. Such changes may be due to reasons politically, economically, or socially advantageous to a community.

Sample Analysis of Language Data

People & Words

People use words to name and describe what they know and do. Because words usually persist in use across many generations, changes over time in the meanings and usages of those words reveal past changes in how people carried out the activities or understood the ideas depicted by those words. It is in this line of study researchers especially examine the histories of those parts of the vocabularies of languages that are of cultural significance and interest both historically and to the modern-day speakers and societies. The histories of these kinds of vocabulary reveal the ways in which past people developed new ideas and shared established ideas. And they also shed light on the ways that languages have changed, persisted, or innovated to suit new historical contexts. As words are added or deleted from particular languages, researchers learn a great deal about people’s thinking and priorities.

Old, Borrowed, or New?

Historian linguists aims to determining whether words in a language are old and inherited, newly innovated, or borrowed from the speakers of other languages. Etymology the study of word history and reveals semantic and metaphorical thinking. Histories of individual words helps researchers to understand how a word or group of words’ structure and meaning can be changed to take on new figurative representations. It is also a way to understand how speakers in different communities adapt a word’s meaning over time to fit new contexts and to communicate their changing social and cultural practices and world-views.

Families, Lineages, and Clans

Concepts related to families, lineages, and clans illustrate that speakers maintained old word stems across many societies – though in a variety of modified formats. Perhaps as early as the proto-Bantu period, 5,500 years ago, *-kódò (see Table 2.1) was a category of social belonging. Two block distributions of *-kódò hold connected but distinct meanings.One connotation is “grandparent” which is used in languages stretching from central west to central east Africa, and the second is “kinship” spanning from northeast to central east Africa. A third block distribution meaning “matriclan” exists in a more geographically and linguistically narrow distribution among Kaskazi and Kusi speakers in eastern Africa. The languages spoken within these block distributions are all Savanna Bantu descendant languages. In many languages *-kódò attests as kolo because in Bantu languages very often /d/ became /l/ due to phonetic shift.

Metaphors

The etymology of *-kódò in two branches of Savanna Bantu, coupled with an understanding about the way people develop metaphors, reveals aspects of belonging historically. Datable to Nzadi-Kwa languages of the early third millennium BCE, *-kódò signified the “base of a tree” or “grandparent”in its earliest concrete meaning. Early Nzadi-Kwa speakers also used *-kódò as a metaphor for “origin” to signify that people belonged to a common base. This explicit concrete meaning of “base of a tree” appears still today in far-flung Mashariki Bantu descended languages. People typically develop concrete meanings before they conceptualize metaphors, so grandparent and trunk of a tree likely preceded the metaphorical use of *-kódò to mean origin.

Maternal Line

One question that remains is whether the grandparent term specifically was more specifically a reference to “grandmother” in its earliest usage. If that were so, then the other two meanings would point toward a grandmother as the root of a lineage and the metaphorical base of a tree. Language data together with the weight of examples from comparative ethnography suggest that since the last millennium BCE, *-kólò implied the unity of ancestors and matrilineal social organization. It seems likely that *-kódò went back to proto-Bantu times with a meaning related to maternal line or grandmother.

*-Kólò & *-Simbi–

The collective body of data suggests that the more structured social meaning of *-kódò was the word for a matriclan in the last millennium BCE. The various meanings points to *-kólò connoting female ancestry as the basis for determining identities and belonging. Distinct from the more general term for ancestor spirit, *-dÍmù, the root *-kódò/*-kólò seems to be more specific to an ancestor spirit affiliated specifically with the maternal line. A semantic change in the meaning and use of *-kólò, which has been dated to the last millennium BCE reflects the value placed on maternal lineage affiliation. Certainly by the last millennium BCE, one group Mashariki-Bantu speakers—the Kaskazi—applied *-kólò to mean “matriclan.”

Creator God *nyàmbe

The intersections among lineage, the spirit world, and authority in Bantu worldviews discussed earlier with the root *-kólò are further reflected in the etymology of the root *-simbi. Based on its geographic distribution, *-simbi emerged as a term about three thousand years ago at the end of the third phase of the Bantu expansions. This root means either spirit of the dead or a young woman during female initiation. These two meanings illustrate an aspect of the early Bantu worldview in which these spheres were entwined. Like the root *-kólò may show in the earliest Bantu eras, *-simbi reflects that while change was underway links between ancestors and the living persisted in the thinking of some communities even two millennia after the proto-Bantu era.

God nurtures *-leza

Bantu religion offers one example for thinking about how people’s ideas change over time. Around 500 CE a group of Bantu-speaking people living in the region of modern-day Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and referred to by researchers as proto-Sabi speakers began to use a new word to signify god. The term Leza reveals a belief in a conception of God or Creator that traces back to ca. 3500 BCE. The emergence of this new term is important because there was already an even older term for God, thus the innovation marks a shift in thinking. There was a proto-Bantu root for creator god was *nyàmbe, from *-amb-, a verb meaning ‘to begin.’ What is distinctive about the etymology of Leza is that it derives from a proto-Bantu verb *-ded– meaning “to nurture” in the way parents or communities care for children. People who used the old Bantu verb root word *-ded– to denote “Creator” were reconceptualizing God, moving away from origins and creation to a concept of care. The shift in meaning however was hardly sudden. It was the outcome of several linguistic steps. One development involved a change in phonemes whereby the shard stop /d/ sound became a more liquid sound /l/. There was also an addition of a causative aspect suffix *-i, yielding a verb *-dedi-. While the initial /d/ shifted to /l/, the second consonant /d/ followed by the vowel /i/ shifted to /z/. Finally, a noun-forming suffix was added to the verb. The result was Leza, a word that signified the idea of God as a nurturer.

Etymology

This etymology implies a shift in worldview among this sub-group of Bantu-speaking people about 1,500 years ago. Leza’s etymology suggests that among the proto-Sabi and proto-Botatwe, the quality of God as a more involved nurturer of creation supplanted the ancient Bantu idea of God as a distant Creator of the cosmos. The glottochronological estimate of the proto-Sabi and proto-Botatwe societies at around 500 CE, combined with archaeological findings dating to that era in the areas around the copper belt of southern DRC in Katanga and central northern Zambia suggest that this shift in the worldviews of a particular sub-group of Bantu-speaking people in Central Africa

Historians

Historians are most concerned with human driven change over time and the processes involved in the transformations. It is important that historian linguists establish a timeline, or chronology to offer a periodization for historical shifts. This provides a framework for historians to suggest how people who spoke those languages conceptualized and transformed their worlds and to establish chronologies through comparative historical linguistic methods. The chronologies of divergence are a tool to establish family trees that reflect the periods in which a given set of languages diverged. Trees reflect origins and divergences, but do not preclude the re-convergence or later encounters among language communities that moved in different social and/or geographic directions.

Linguists

Morris Swadesh (1909–1967) developed a provocative standard for estimating dates for language divergence. He called this use of lexis (vocabulary) to create a chronology lexicostatistic glottochronology. Using statistical comparison of the rates of replacement, in pairs of diverging languages, of old words by new words for each meaning in a core set of one hundred very basic words—called basic or core vocabulary—researchers can propose estimates of about how many years before the present (BP) the divergence between the languages began. A time-depth chart that conveys how Swadesh predicted that change might look over time is represented in Table 1.1. The larger the percentage of core vocabulary that languages share between them, then the more recently they are hypothesized to have diverged from an ancestral language. Exact dates for language diverge from an ancestor cannot be definitively claimed, but glottochronology allows us to propose a chronological order for language divergences and the broad time ranges in which a language diverges and becomes its descendant languages.

Divergence

Swadesh theorized that language divergence develop gradually over decades and centuries as communities of people speaking a common language moved further apart socially and quite often geographically. He maintained that as speakers of a language had decreasing or increasing contact, over long spans of time, their vocabularies would capture the interaction or divergence in the ways languages changed. Continued cohesion within a community of speakers would result in the maintenance of mutual intelligibility because changes would be adopted mostly everywhere in the community.

Core Vocabulary

Conversely, reduced contact among speakers leads to increased dialect difference. Adoption of new words for core vocabulary meanings would presumably spread consistently to nearby communities speaking the same language but perhaps not to more distant communities. Communities in different areas often develop different ways of pronouncing what were originally the same vowels or consonants. Slowly over time and space, these lexical and pronunciation variances accumulate, and the emerging dialects become more and more distinct from each other, eventually becoming no longer mutually intelligible. When mutual intelligibility becomes too challenging, dialects become distinct languages.

Database Uses

The database developed for this project was designed to provide the kinds of language data that is useful in understanding early histories of families, generations, and genders, but is not limited to these aspects of life. We hope that the data we provide together with data you have collected will be deployed to write many early histories of life in eastern, central, western central, and southern Africa where Bantu speakers have built communities. Link to the the database.

Sources

- Bybee, Joan. Language Change. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

- Crowley, Terry, and Claire Bowern. An introduction to Historical Linguistics. 4th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Ehret, Christopher. “Testing the Expectations of Glottochronology against the Correlations of Language and Archaeology in Africa.” in A. McMahon C. Renfrew and L. Trask (eds.), Time Depth in Historical Linguistics, vol. 2 (Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2000), 395.

- Fischer, O. “What Counts as Evidence in Historical Linguistics,” Studies in Language 28, no. 3 (2004): 710–740.

- Fourshey, Catherine Cymone, Rhonda M. Gonzales, and Christine Saidi. Bantu Africa (Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Fourshey, Catherine Cymone, Rhonda M. Gonzales, and Christine Saidi. “Leza, Sungu, and Samba: Digital Humanities and Early Bantu History.“ History in Africa Volume 48, (2021); 103-131.

- Klieman, Kairn. The Pygmies Were Our Compass: Bantu and Batwa in the History of West Central Africa, Early Times to c. 1900 C.E. Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann, 2003.

- Lehmann, W. P. Historical Linguistics: An Introduction, 3rd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2013), chap. 9.

- Walker, Robert S., and Marcus J. Hamilton. “Social Complexity and Linguistic Diversity in the Austronesian and Bantu Population Expansions.”Proceedings: Biological Sciences 278, no. 1710 (2011): 1399–1404.